Published on

A new lens on corporate net zero

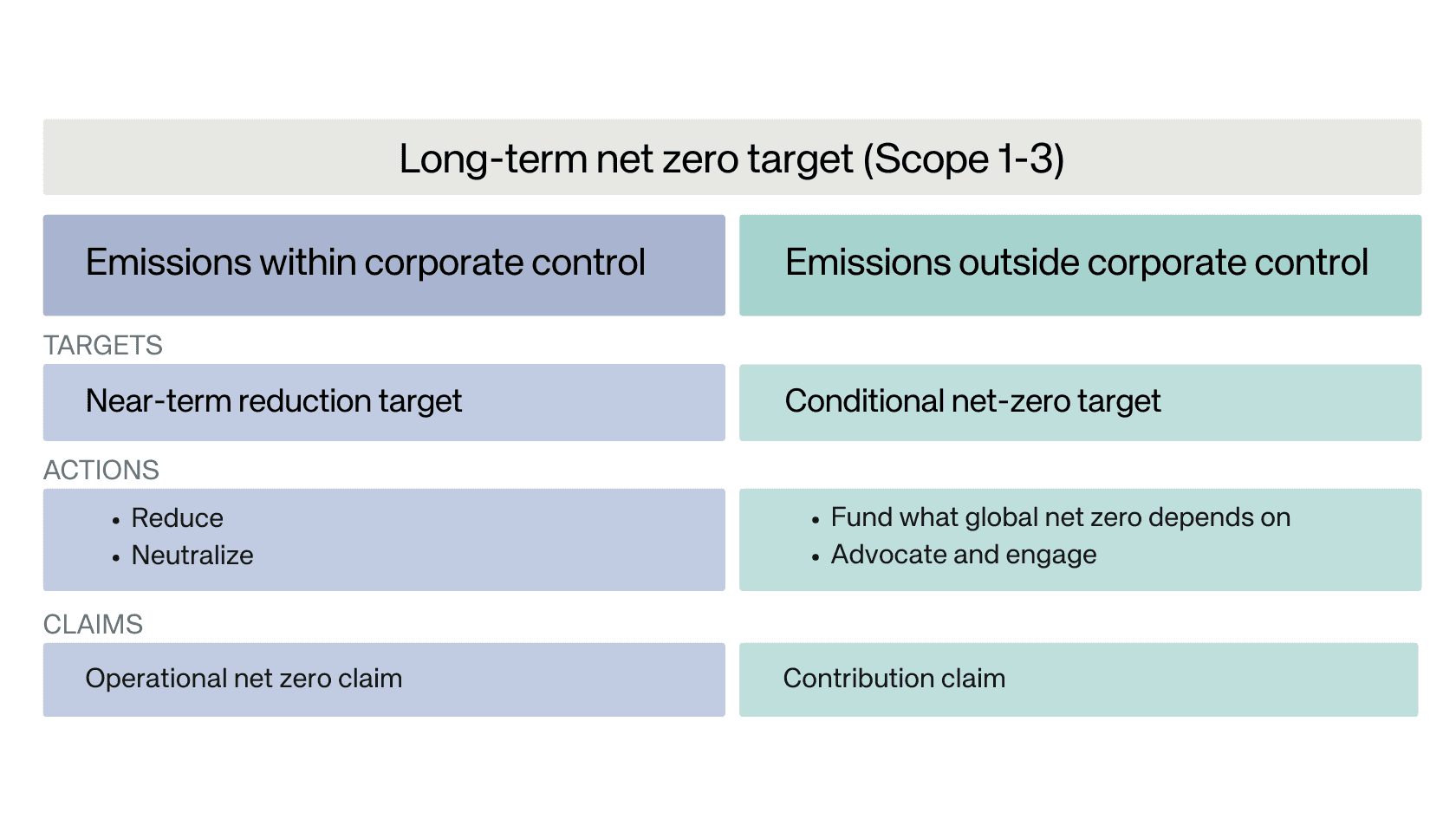

Net zero targets blur the line between what firms can directly control and what requires wider systemic change. This article introduces a new lens for clarifying responsibility, action, and claims under corporate net zero.

Robert Höglund

Head of Climate Strategy & CDR

Net zero targets have become the default for companies, with around 29% of all listed companies now having one. That’s good. If the world is to stay below 2°C of warming, global emissions must reach net zero. But the way net-zero targets are treated today is simultaneously setting companies up for failure, inhibiting action, and obscuring what matters most.

Many companies have a hard time making credible plans for how they can meet their net-zero targets. The problem is not ambition, but that targets bundle emissions companies can directly control with reductions that depend on broader system change.

When all emissions are treated as equally deliverable, corporate responsibility becomes unclear and the role of policy and market transformation is obscured. A new lens is needed to make net zero actionable and credible.

Some emissions reductions can be delivered today or in the near future. Companies can change production processes, buy renewable energy and materials, reduce resource consumption, switch suppliers, or influence them to make reductions. These are emissions within a company’s control.

Other reductions are outside companies’ control, or for some companies too expensive to deploy without carbon pricing leveling competition. Examples include emissions deep in the supply chain or electricity use in markets without clean grids. These reductions require system change: policy, infrastructure, markets, and innovation that no single company can deliver on its own.

Importantly, these reduction abilities differ greatly between sectors and do not map cleanly onto GHG scopes. For some vertically integrated, high-margin companies, much of Scope 3 can be within operational control. For some low-margin, hard-to-abate sectors, large parts of Scope 1 may be outside of control when financial ability is taken into account.

Treating these different parts of corporate net-zero targets as equally deliverable sends unrealistic expectations to stakeholders and policymakers. It can leave companies demotivated when targets become unachievable and progress depends on factors beyond their influence. And it obscures the crucial role of policy change.

Net-zero targets are conditional

Corporate net-zero targets should be understood as two distinct commitments:

First, what most companies already have: a near-term reduction target covering emissions within corporate control. These are emissions where companies have agency, and where reductions can be delivered through operational changes, clean energy procurement, and direct purchases.

Second, a conditional net-zero target covering emissions that depend on changes outside corporate control. These reductions will only happen if the broader system transforms: if policy shifts, infrastructure gets built, and roadblocks are eliminated. How large the conditional share is differs enormously across sectors and business models.

Making this distinction explicit does not weaken net-zero targets or shield companies from responsibility. It clarifies what net zero actually requires: direct responsibility for what you control, and active contribution to the system change you depend on.

Different targets require different actions

For emissions within corporate control, the actions are familiar.

Companies should reduce emissions as much as possible, as fast as possible, through a wide set of measures. For remaining emissions, companies can use durable carbon removal to neutralize them and optionally make “operational net-zero” claims. Many companies already have such 2030 operational net zero targets for Scope 1, Scope 2, and often business travel emissions.

For emissions outside corporate control, the actions are different. By definition, these emissions cannot be reduced through company action alone. Instead, companies need to:

Clarify what policy change and technical development their targets depend on, and make those dependencies explicit.

Advocate for the policy changes their targets assume will occur. If a company’s net-zero goal depends on carbon pricing, grid decarbonization, or permitting reform, it should openly support those changes.

Fund the conditions their targets depend on. The highest leverage lies in funding what unblocks progress: policy reform, regulatory fixes, proof-of-concept deployments that de-risk markets, and institutional capacity that allows cheap solutions to scale. Other solutions show promise but need to be unlocked by coming down in cost, such as advanced biofuels, green steel, alternative materials, and carbon removal.

For this kind of funding, claims of contribution to global progress are appropriate, rather than claims of carbon neutrality.

This framing aligns with where standards and guidance are moving. Draft SBTi guidance now urges companies to take financial responsibility for their emissions and requires disclosure of whether they fund climate action beyond their value chains. Frameworks such as Oxford Net Zero’s Spheres of Influence, WWF/BCG’s Blueprint for Corporate Action, and New Climate Institute’s Climate Responsibility approach all emphasize that internal reductions alone are insufficient and that companies must contribute to broader mitigation.

This is what net zero really is: a mix of direct responsibility and system dependence. Companies must act on what they can change today by taking responsibility for ongoing emissions under their control, and help enable the world their targets depend on by supporting the broader changes required for Global Net Zero.

This lens does not let companies off the hook, it replaces vague long-term promises with concrete near-term action and honest acknowledgment of dependencies. It helps companies focus on what they control, while exerting their influence to change the things they do not.

Importantly declaring emissions conditional increases, not decreases, the obligation to fund and build the solutions that resolve those conditions.

This is a clarifying overlay on existing standards, not a replacement. It is meant to increase ambition by making explicit what we can expect from different companies, and what external change is needed.

In forthcoming articles, we will go deeper into how conditional net-zero targets can work in practice, on operational net zero, and how corporate climate action can be assessed in light of what companies control and what they depend on.